The Knorr never sleeps. So neither do the scientists on it — or at least not all at the same time. Between sunrise and sunset, two “watch standers” and one marine tech are engaged in a data-collection all-nighter.

Sunday was the fifth night shift of our cruise, the night of the full, close-to-Earth moon, and the night that I chose to sit in. Close to Greenland, we were cruising over the continental shelf: the water is a little shallower here, the currents more interesting, and the work of the watch standers faster-paced.

Preparing to drop the rosette into the ocean at the beginning of the night.

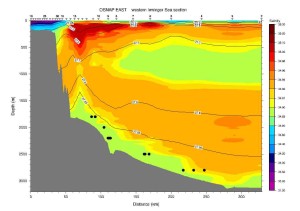

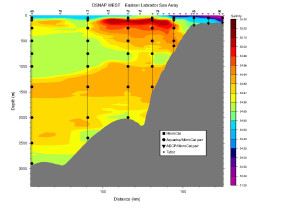

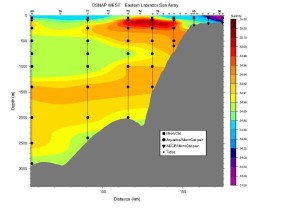

The primary job of the watch standers is to usher a heavy and expensive instrument — called a CTD rosette, for its shape — to the bottom of the ocean. When watch standers Robert Daniels and Mironov Illarion take over at 8 PM, the thing is about 1,000 meters underwater, and rising at 60 meters/minute. Every couple hundred meters it stops, they hit a button that says “fire bottle” on the screen, and it closes one of its grey tubes to add 10 liters of ocean water to its load. Then one of them will press “talk” on a speaker box and tell an operator to bring the rosette up to a new height. Along its journey, sensors on the rosette measure the salinity, temperature, and density of the water: the “fingerprint” of a current. A lab tech, Elizabeth Bonk, will analyze the salt samples collected by the bottles.

This procedure — a CTD cast — is a staple of oceanography. Illarion and Daniels have both done the casts before — Illarion in the Arctic, and Daniels off the Bering straight. The CTD data they collect here will contribute to a high-resolution snapshot of what the current around Greenland is doing.

Creating this snapshot is, for now, an act of construction work. Illarion and Daniels have showed up to work in steel-toe boots; they add hard hats and orange life-vests to their safety ensemble. (Illarion is also wearing neon yellow overalls, his own sartorial contribution to the “safety” look.) When the rosette returns to the surface, we go outside, and stand on the deck. It is 50 degrees, plus wind chill. Nicholas Matthews, the marine tech on duty tells me to stand inside the garage or put on a hard hat — so he doesn’t get in trouble.

The rosette, on its wire line, emerges from the water. The watch standers hook the metal frame of the rosette with poles longer than they are tall. From a control room above, an operator recoils the wire, and retracts the metal beam that it is hooked on so the rosette swings onto the deck of the boat, and lowers onto a little wooden platform. The watch standers strap it in, and then, with the pull of a lever, the platform moves the rosette from the deck into a little garage, where I am standing. Beneath the light of a heat lamp, Illarion sprays the frame down with a fresh water hose. He and Daniels collect salt samples from each of the six bottles that they fired during the cast.

We go back inside, and then, maybe half an hour buy lasix online later return to the deck-garage to do the reverse: the watch standers move the rosette onto the deck, unstrap it, and the operator lifts it into the ocean. From the control room, we wait for this piece of machinery — which, for all the world, looks like Iron Man’s heart or a slice of a particle collider — to make its way to the bottom of the sea.

Continue reading →