By Emma Brown, Boston College student

We arrived in Woods Hole! We immediately began lashing down anything that exciting seas might send sliding. This included various boxes of scientific materials, including our toolbox, with bungee cords and ratchet straps. Our filtration system was placed on a sticky mat and bungee corded in both directions. Other boxes, some meant to hold future samples, were lashed in place in the cooler atop metal racks.

This morning, all hands were on deck to help board stores! A large crane lowered cloth nets bulging with boxes of goods into the ship, directed by crew members in hardhats. Once the goods had reached the floor, these crew members freed the net from the holding hooks and cut the boxes loose from their plastic packaging. Then, almost all crew members and scientific personnel formed a passing chain to help load frozen, refrigerated, and fresh stores onto the Neil Armstrong. The process was amazing! Everyone worked as an oiled machine as the galley quickly filled with boxes upon boxes of assorted goods. Our second mate, Chrissy, worked as fast as she could to fit these boxes jenga-style into a food elevator to put them into the ship’s massive freezer/refrigerator.

We began our journey across the Atlantic! We were on the boat by 9 am and met for a team meeting and safety training at 10 in the main lab. The 1st mate, Chris, explained the protocols for fire and abandoned ship. Ayden demonstrated how to don a life-saving wetsuit. It’s not very complicated after you’ve been shown how to do it (I also had to try mine). I was just a half inch too tall for a small- apparently, they’re made for people exactly 5’4 and under. The next size up must be made for people about eight feet tall because I was practically swimming in it. One must lay this suit on the floor to climb into it, one limb at a time. Chrissy, the third mate, helped me get my arms and legs inside. The suit may be zipped up past one’s chin and a strap is placed over the lower part of one’s face. The final step is to squeeze all the air out by crouching and hugging one’s knees. The suits are enormous and clunky beyond imagination, but life-saving in an emergency.

At noon precisely, the boat was pushed away from the dock and we all waved goodbye to those we were leaving behind on land. Following departure, we did drills for emergencies. For a fire, everyone met in the main lab. For abandoned ships, top bunk people rendezvoused at the port side of our vessel and bottom bunk people convened at the starboard side. Later in the evening, the boat stopped for our first CTD cast! In hard hats, steel-toe boots, and bibs (foul weather gear, lacking the jacket), we undid the ratchet straps anchoring the CTD in place on the deck. A well-oiled crane picked the CTD up on a thick cable. The tension in the cable was visible via a screen well over our heads. The tension rapidly increased as the CTD was lowered over the water. We popped all of the Niskin bottles open on top and bottom. These “fired”- aka, closed- once the CTD reached the desired depth at 165 meters down.

The machine was then slowly pulled back to the surface on its cable and gently lowered onto the boat, dripping seawater. We quickly strapped it back to the deck. Then, we tested each bottle to be “leakers,” meaning it’s a Niskin that did close properly on the way up therefore, it’s bad water and can’t be used for science. We took samples for DOC (dissolved organic carbon) and POC (particulate organic carbon). Both involve rinsing the sampling bottle and cap out 3x, then filling to the top with seawater from the desired Niskin. Immediately after, in the lab, we practiced filtering both types of samples.

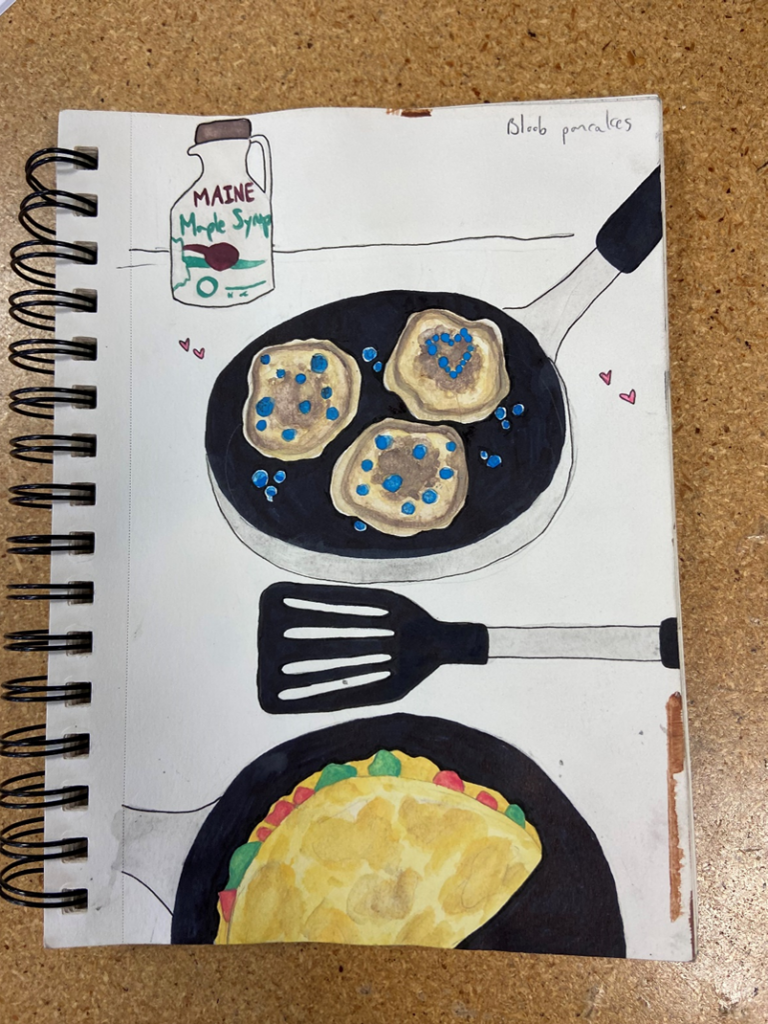

Photo: The author spends free time on the transit painting and drawing each day.