By Aurora Roth

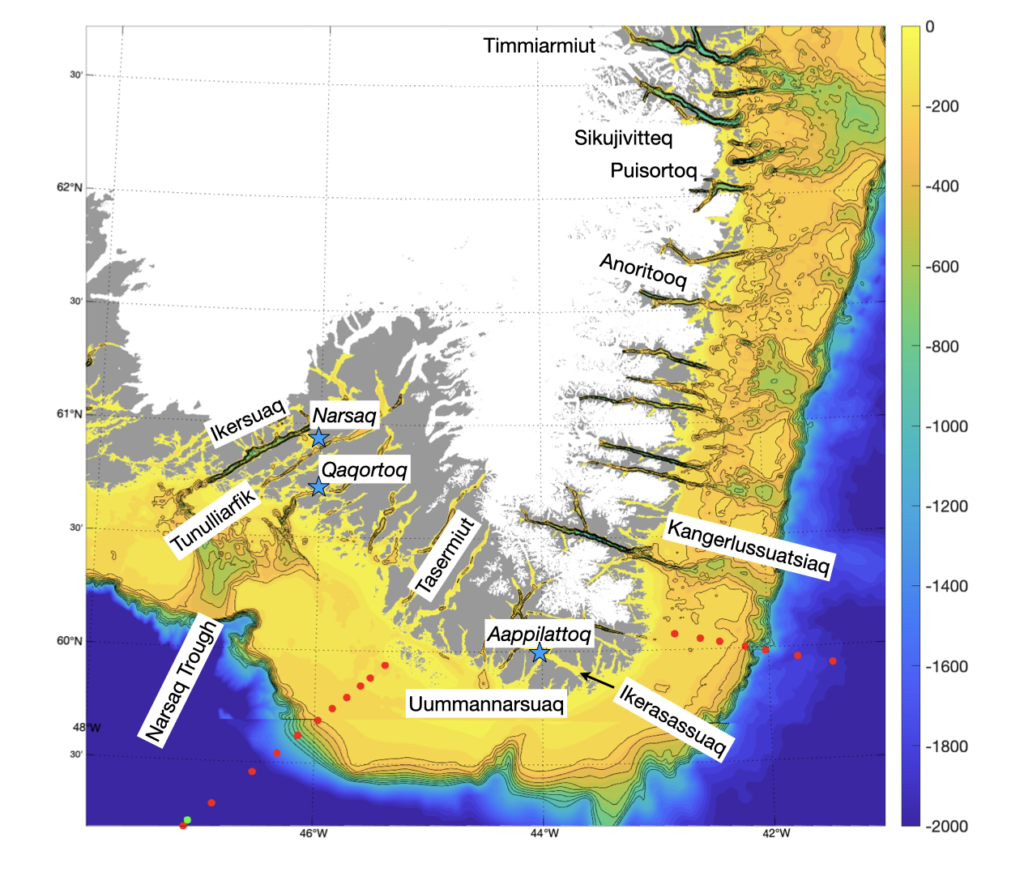

On September 1, almost halfway through the cruise, we passed through Ikerasassuaq (“big sound”, alternately known as Prince Christian Sound). It’s a long narrow channel that demarcates the north end of Uummannarsuaq (“large heart-shaped place” or Cape Farewell), at the southern tip of Kalaallit Nunnat (Greenland). Travelling through this fjord marked our transition from work on the southeast coast and the Cape Farewell mooring array to work on the southwest coast and the Labrador Sea mooring array. Until this, we had been moving up and down the southeast coast (see map for cruise track), completing hydrographic surveys, taking water samples, and replacing long-term instruments that will live in the depths of the ocean taking measurements for the next two years. The coasts, seas, glaciers, histories, and settlements of the southeast and southwest regions are wildly different, and going through Ikerasassuaq felt like going through a portal to a different world.

We followed a cargo ship into Ikerasassuaq, bound for Qaqortoq (“white”), the largest town in the south of Greenland. We saw the lights of Aappilattoq (“the reddish place”), the first town we’ve seen as we stopped in the sound for the night. In contrast, the southeast coast has no towns, though there are archeological sites of older settlements. The southeast coast, with its steep mountains and glaciers plunging into the ocean, isn’t the best place for permanent towns, but it used to be travelled often by people from further north around Ammassalik (“the place with capelin”). From Ammassalik, people would travel south and around the bottom of Greenland to the west coast to trade and meet up with West Greenlanders. As the east coast was colonized, a Danish trading post and mission were set up in Ammassalik. Travelling along this part of the southeast coast stopped as trading with Denmark replaced travelling to trade with West Greenland. As a consequence, East Greenlanders became even more isolated from the populous western side (Gulløv 1995). Now, the few people that follow this coast and navigate around the icebergs here are from adventure sailing and climbing expeditions and the occasional research vessel, like us. For almost two weeks we didn’t see any other vessels. There is also a lasting separation between East Greenland and West Greenland, and East Greenlanders are often marginalized, with less access to resources, fewer education opportunities, and less power in the national government.

I’ve been wondering what knowledge, place names, and connections have been lost here along this stretch of coast as a result of colonization. Documented Greenlandic place names are sparse here, but what I could find (mostly from a report by the Danish Geodata Agency, reviewed by Oqaasileriffik, the Greenlandic Language Secretariat) made this coast feel more animated. The place names show how Greenlanders gave their attention to and were in a relationship with this stretch of coastline – Timmiarmiut fjord and glacier means “habitation of the birds”. Sikuijivitteq means “where it is never free of ice”. Puisortoq glacier means “how often something comes to the surface” but also “puisi” is a word for seal and perhaps this is related? Anoritooq glacier and fjord, meaning “where it is very windy”.

Our furthest north point was Timmiarmiut fjord. We surveyed the underwater trough that extends beyond the fjord onto the continental shelf. This trough, and others like it, were made over 10,000 years ago when the sea level was lower and glaciers of the ice sheet extended further. After sending our instruments down into the water above the trough, we watched squiggly lines form on the screens in the lab. These data tell us that cold water with a temperature below 0°C was following the trough out into the ocean but near the surface, and warmer water (3-4°C) from the North Atlantic and Gulf Stream was flowing into the bottom of the trough. We call the cold water “Polar Water” and it’s a mix of glacial ice melt, sea ice melt, and water from the Arctic Ocean. Its freezing point is below 0°C because it’s salty ocean water despite being less salty than other ocean waters. The Polar Water and warmer Atlantic water come together and intermingle at different depths, trying to figure out where to go as they meet each other and mix. We collected data at other fjord outlets and troughs as we came back south along the coast. Each time we saw this layering of colder, fresher water, sitting above warmer, saltier water and saw thin layers of each water type trying to weave together. The outcome of this meeting and weaving is what controls how much warm water can come into fjords and contact glaciers causing further melt, and how much glacial meltwater can then come out of fjords and mix into the North Atlantic Ocean, affecting large-scale ocean currents and climate.

From velocity measurements taken with Acoustic Doppler Current Profilers (ADCPs), we started to map out how these troughs make the East Greenland Coastal Current wiggle and turn, further complicating this meeting of different waters. Even when hundreds of meters deep, the ocean can “feel” the bottom topography and responds to it by changing course. Sometimes in the data, we could see eddies generated from the troughs that were swirling in circles, causing water to mix. To make things even more complicated, we experienced two days of strong winds while collecting data. The winds pushed the surface of the ocean around causing waves and more mixing of water. When the winds blow from north to south, this sets up the physics of the ocean to push the warmer water closer to the coast. When I step back and take this all in, there is so much movement and action at every scale. Everything affects everything else. It’s sort of amazing that we can make any sense of the data we collect at all, that we can figure out stories of what’s happening here and why it matters.

Many of the glaciers along the southeast coast have transitioned in the last two decades from ending in the ocean to now ending on land, retreating up into valleys, deflating from their moraines, and separating into different branches. When a glacier loses its direct connection with the ocean, it changes how the glacier meltwater mixes nutrients into the ocean and it changes the marine ecosystem. One of the things we’re doing on this cruise is collecting water samples to analyze for nutrients (like nitrate, phosphate, silicate, etc) to understand this story better. The Greenlandic place names speak to these ecosystems supported by glaciers, of the birds and seals (even the winds which are impacted by glaciers). I wonder how long the place names that remain will continue to describe these places, or even if they still do.

We are here now in Kalaallit Nunaat, as western-trained scientists trying to understand certain stories of this place. Greenlandic people and culture have stories of this place too that are equally important. Sometimes glimpses of those stories are found in the Greenlandic place names. The small act of putting in effort and time to figure out place names, and use them in conversation, outreach, or academic publications, is a small act of acknowledging Greenlandic presence and relationship here. It’s also an act that acknowledges what was violently lost due to colonization and what stories and names have persisted despite it.

Learn More

Greenland Pilot – Explanations of the Place Names from the Danish Geodata Agency

- https://eng.gst.dk/media/9097/gp-explanations-of-the-place-names_2015_skr_27_2020.pdf

- https://eng.gst.dk/about-us/news-archive/2020/the-danish-geodata-agencys-publications-on-navigation-in-greenland-waters-are-now-all-digital

More on Greenlandic Place Names

- Oqaasileriffik, The Language Secretariat of Greenland

- Bjørk, A. A., Kruse, L. M., and Michaelsen, P. B.: Brief communication: Getting Greenland’s glaciers right – a new data set of all official Greenlandic glacier names, The Cryosphere, 9, 2215–2218, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-9-2215-2015, 2015.

References

Hans Christian Gulløv. Olden times in Southeast Greenland: New archaeological investigations and the oral tradition. Études Inuit Studies Vol. 19, No. 1, Archéologie, Art, Ethnicité (1995), pp. 3-36.

Morlighem M. et al., (2017), BedMachine v3: Complete bed topography and ocean bathymetry mapping of Greenland from multi-beam echo sounding combined with mass conservation, Geophys. Res. Lett., 44, doi:10.1002/2017GL074954, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2017GL074954/full