September 12, 2018

by Isabela Alexander-Astiz Le Bras

Two weeks ago we left Reykjavik on the R/V Neil Armstrong for the last OSNAP cruise of the season, a five week expedition to the outskirts of Greenland. Our goal: “turn around” two sets of OSNAP moorings and taking as many CTD casts as possible. In fact, Chief Scientist Bob Pickart is well known for taking particularly large numbers of tightly spaced CTDs.

Every group will say this, but I think our region is the most interesting of the OSNAP array. East of Greenland, cold and fresh water from the north meet warm and salty waters that originate in the Gulf Stream. This place is a turning point for the ocean’s global overturning circulation, which helps stabilize the earth’s climate, yet measurements here are severely lacking, partly due to the conditions I will describe here.

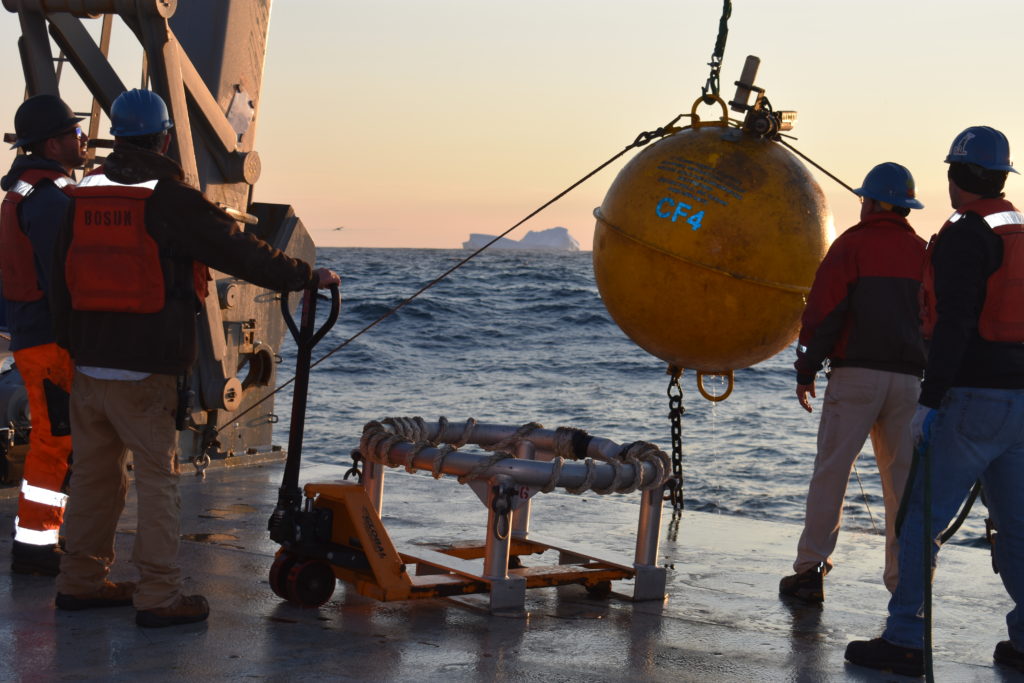

You may already know all this, but I’ll start by getting you up to speed on oceanographer-speak just in case. Moorings are long wires dotted with instruments that are anchored to the sea floor and take measurements for as long as several years. We are picking up our moorings after a two year deployment and are only able to access the data in the instruments once they are on board. We are also deploying a new set of moorings to leave in the ocean for another two years. The moorings we are servicing range from 100m on the shelf to almost 3km long offshore!

The CTD (conductivity, temperature, depth) rosette is the workhorse of oceanography. This instrumentation package measures temperature, salinity and pressure/depth as it is lowered through the water column by a winch on the ship. It also includes Niskin bottles that are closed at various depths to collect water that is used for calibration and ADCPs (Acoustic Doppler Current Profilers) that measure ocean velocity. Our CTD package also includes a set of chipods, which Jonathan Nash from OSU very generously loaned me for this cruise. Chipods measure temperature gradients at high speed (100 measurements per second), providing a quantification of turbulent processes over centimeter scales. As our CTD sections survey ocean properties at finer spatial resolution than the moorings, we use these to learn about detailed ocean dynamics and to ground-truth the mooring measurements.

Our first priority on this cruise is to retrieve and re-deploy the OSNAP moorings. However, this can only be done in daylight and when it is calm enough to be lifting large objects in and out of the ocean. A group of mooring specialists from WHOI and the Armstrong’s deck crew physically deploy and retrieve the moorings while others (like myself) take notes. To take full advantage of being out here, anytime that we can’t do moorings, we are doing CTDs. And by we, I mean a small army of graduate students, postdocs and technicians who take 8 hour shifts round-the-clock to operate the CTD. Of course, none of this work is possible without the ship’s crew who get us where we need to go and keep us safe on our floating home for these 5 weeks.

I thought I knew what to expect, having been to sea several times before and having spent the better part of the last year analyzing mooring data from the first deployment. I was also fully aware that we were heading into stormy seas pretty late in the “calm season”. After all, we think the currents we are studying are driven by the winds that zip along the coast of Greenland and flare up at its ominously named southern tip: Cape Farewell.

During the first few days that reality set in as we rocked and rolled our way to our study site. For me at least, there is a difference between knowing its a stormy region and being tossed around in my bunk for 24 hours. Our chairs slid across the main lab as we gathered to discuss plans and even the most seaworthy in the crew held on tight as they staggered down the hallway. It didn’t always feel great, but it sure helped me internalize that this really is one of the windiest places on earth.

Once on the continental shelf of Greenland, we were greeted by stunning views and large craggy icebergs that were well worth the weather. During the first OSNAP deployment (2014-2016), the inshore-most mooring, CF1, was hit by such an iceberg and the instruments sitting at 50m and 100m fell to the seafloor about a year after deployment. While marveling at their beauty and size, I wondered how such iceberg casualties were not more common. Luckily, we managed to recover CF1 this time as well, though yet again the 50m instrument was knocked down to 80m less than a year into the deployment.

For the rest of our stay east of Greenland we alternated between mooring recoveries and deployments, doing CTDs through the night, and hiding behind the cliffs of Greenland when the weather turned. Our mooring operations were successful with the exception of one mooring on the shelf that has refused to surface thus far. We will be back for it as soon as we are done with the rest of the moorings, but it stands as a painful reminder that what we are doing here is difficult, and that the ocean is full of uncertainty and surprises.

Two days ago we crossed through the beautiful Prince Christian Sound to start all over again west of Greenland. Armed with successful mooring operations east of Greenland, two sections of CTDs and two weeks of experience working as a team, I think we are ready to take on the Labrador Sea!

Recovering the flotation sphere for mooring CF4 with an iceberg in the background. Pictured from left to right: Andrew Davies, Pete Liarikos, John Kemp and Brian Hogue.Photo by Isabela Alexander-Astiz Le Bras

The last step of mooring deployment is dropping this anchor off the fantail to the seafloor.Photo by Isabela Alexander-Astiz Le Bras