The largest water fall in the world is an underwater waterfall. Its just northwest of Iceland, and it begins with water spilling over an underwater ledge between Iceland and Greenland, the Denmark Strait.

Hurtling down this water fall are cyclones of water, 1,500 meters high.

Bob Pickart was the first to measure the cyclones in 2008. He measured them by accident: They spent a year whacking into 4 stationary vertical strings of instruments that he had placed in the ocean. These moorings were at the bottom of the waterfall, a checkpoint to see what it did after it spilled off. When he went to collect the data— a year’s worth —he found that it was garbled. Instead of examining a vertical slice of the ocean, the instruments had been repeatedly pushed over at an angle. What emerged from the mess was a picture of a tornado-like column of water, rushing past about once every two days.

This is how they form: As dense water moves over the Denmark Strait, it sinks. (It does this over the course of 100 of kilometers —though taller than Niagra falls, this under water water fall is not a steep waterfall.) As that water sinks, it starts to spin —kind of in the same way that a figure buy hydrocodone online skater hugs her arms to her chest to spin faster. The result: a towering, whirling column of water.

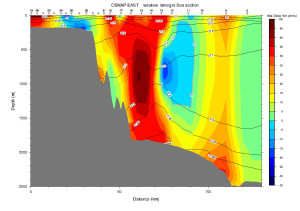

If you measure its velocity, it looks like this:

The red part is coming at you at 80 cm/s, the blue part is going into the screen at 30 cm/s (slower, because the whole thing is also moving southward.)

The above is a snapshot of a cyclone just off the coast of Greenland. It was big surprise: we were 600 miles from where the cyclones form. Pickart thought that they must have spun apartlong before this point.

In fact, oceanographers had gone over this section of ocean dozens of times before. This cruise captured the cyclone because we stopped very frequently to take measurements. (“That’s Bob’s style,”observed a lab tech late one night, as the watch standers went outside yet again to drop equipment into the ocean.)

How did the cyclones survive for so long after they formed? Are there lots of them 600 miles from the Denmark Strait? Where do they end up?

“Well, that’s the whole question,”says Pickart. A closer look at these cyclones will help answer one of the big questions of OSNAP: where dense water goes, and how it goes about getting there.